Who Dat?

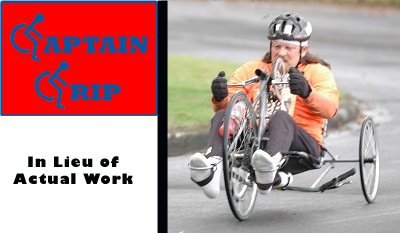

Back in the 80s, long before the X-Games existed, Tom Haig traveled the world as an extreme athlete. He visited more than 50 countries as an international high diver, doing multiple somersault tricks from over 90 feet.

That life came crashing down one Sunday morning in 1996. While training on his mountain bike, he smashed into the grill of a truck and became paralyzed from the waist down. But less than a year later he completed a 100-mile ride on a hand-cycle and traveled by himself to Europe and the Middle East.

Since then he has continued to travel the world as a consultant, writer and video producer. He spent six months launching a Tibetan radio station in the Himalayas and shot documentary shorts on disability in Bangladesh, France, Albania, Ghana and most recently Nepal.

Thursday, March 30, 2017

20 Pools - A Swimming Odyssey: Pool # 12: Himalayan Villa, Pokhara, Nepal

Monday, March 27, 2017

20 Pools - A Swimming Odyssey: Pool # 11: Club Bagmati, Suryabinayak, Nepal

Oddly enough, on my way to work (the hospital DID have an accessible bus) we went past a sign for a resort pool in my neighborhood. My sister, Nikita, told me the pool was way too high up the side of the mountain for me to get to - that I would need a taxi in order to go there. But like nearly every bit of information I got in Nepal, there where bits and pieces of facts surrounded by tons of speculation.

The truth of the matter is that Nikita didn't know how to swim and had never been to the pool before. Just three weeks before I was to leave Nepal, Nikita told me she went to the pool and she thought I could probably get there. She said she and three of our co-workers from the hospital were taking swimming lessons after work.

At first I was angry because I could have actually been working out every day after work. The pool was less than two miles from our house. But seeing as it was winter, it had only recently opened up. Winter in Nepal is a relative term. I arrived the second week of February and was never even once tempted to wear anything more than a t-shirt. For me, swimming in an outdoor pool in "The middle of winter" would have not been a challenge. At the Osborne Aquatic Center back in Corvallis, they keep the outdoor pool open all winter and use it as the warm-up pool for high school meets - even in freezing weather.

But no matter how much I would have protested, people weren't going to show up at that pool until May. Nonetheless, the neighborhood pool was open and I was going! Nikita and the group of women from the hospital escorted me up a steep, but short road up to the Club Bagmati pool. It was a nice workout, but nowhere near as difficult an assent as the Sherpa pool or even climbing to the temple at the end of the street we lived on.

Getting up to the pool wasn't a problem, but everything else was. My new neighborhood pool was the worst, least-accessible full-sized pool I'd ever been to. The locker rooms and toilets were up five steps and their doors were too tight for my chair. I rolled up against a row of bushes and nonchalantly changed into my suit. I wasn't really blocked by anything, I just became an elephant in the room. And it's not like public nudity is accepted in Nepal - it's super shocking. But being in the chair, I just assumed people would get my situation and not make a big deal of it - which they did.. kinda. It still freaked 'em out, but they just had no idea what they could do about it.

I was ready to hop in the pool, but the pool wasn't ready for me. The pool was on a raised deck that had to be accessed by a smaller rinsing pool. It was three steps down into the rinsing pool, followed by five steps back up to the deck. Nikita and her friends (who are all very good-looking I might add) had no problem convincing a band of men to come over and help me through the obstacle. For some reason, lifting people in chairs in Nepal is ten times more complicated than it is in the States or Europe. When I ask for assistance in America I'll get two guys, tell them how to do it, and they go. But in Nepal and India it is a huge committee decision and one I don't have a vote in. They discuss it on the side, then start grabbing wheels and body parts until I have to yell to make them stop. Eventually they will listen and I'll show them what needs to be done - but it never happens on the first try. And given the same situation the next day, the same group of men will go right back into their committee and start all over again. It never fails.

Eventually, I made it to the pool deck only to discover the Club Bagmati pool, my new home pool, was a complete piece of shit. It was a 35-yard arcing pool with no lanes and a two-foot deep shallow end. It was full of thrashing teen-agers none of whom could actually swim. I flopped into the deep end and tried to swim a few laps, but it was impossible. I got cannonballed twice and even had one drowning woman grab on to me as she had ventured too far from the side of the pool.

Instead of trying to workout, I joined Nikita and our friends to give them swimming lessons. One of the women took to the water fairly well, but the other four were panic-stricken and thrashing. Nobody knew how to breathe and they didn't really feel like listening to me when I tried to show them. To them swimming was akin to witchcraft and anyone who did it was defying the laws of physics. No matter how I pleaded for them to watch and copy my stroking, they just kept up their panicky thrashing. Getting Nepal to learn the crawl would not come easily.

Although the first attempt at the Club Bagmati was less than positive, I didn't give up. My video project at the hospital was finishing up and there was no reason for me to go to work if I didn't have a film shoot scheduled. During the last three weeks I ended up going up to the pool in the middle of the day when it was nearly empty. I wore my suit to the pool so I didn't have to dress in public. I found a group of workers at the club and trained them how to carry me up and down the steps to the pool. With the pool almost entirely to myself, I could bisect the arc into a 30-meter straight line. I got back to cranking out my mile workout. Even though I was breathing in some caustic Kathmandu air, I was getting back into shape.

One thing I discovered when swimming in Malaysia is, unlike the bike, swimming is a sport you can bring with you anywhere you go. Even on vacation.

| Which brings us to vacation and Pool # 12: Himalayan Villa, Pokhara, Nepal |

Thursday, March 23, 2017

20 Pools - A Swimming Odyssey: Pool #10: Novotel, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Suryabinayak looks nothing like an American suburb, but there was one striking similarity to Lower Clovernook: bands of kids played in new housing constructions. When I came home from work I was mobbed by kids who wanted to play soccer, sing songs and make forts out of the new housing projects. Unlike Clovernook, however, these houses were four to five story brick castles that might house multiple generations of the same family. In Wisconsin we pined the loss of the big fields as housing projects grew, but we still had massive yards. But Suryabinayak is on the side of mountain and houses took up all the flat land that made up cricket and soccer fields. One day a house started going up on the lot next to my family's house and it was devastating to the neighborhood kids. That happened in Clovernook as well. We had a massive field where we would ride our bikes and play football and baseball. One by one it got eaten up by new houses until one year it was just gone. I knew the pain on these kids' faces.

But what they'd developed while playing in those empty lots couldn't be stopped. These kids and these families had developed into a strong neighborhood community where anyone was welcome in any neighbor's house - just like Clovernook. The big kids (12-13 year olds) looked after the little kids - some of them still in diapers. It's something I miss about America and something I was incredibly familiar with. I could have just gone home to my room every night, but being part of this community was a privilege. I fell into a more natural state - not as an adult, but, for the first time in my life, as one of the big kids.

Belonging to that community was never so ingrained as the day I took my first trip away. My brother Andy and I have spent years working with the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (ISPRM). I spent a decade as their web master and Andy was at one point the cheif North American board member. This year we would be attending their annual convention only a stone's throw away in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Seeing as nobody in the neighborhood had ever even been on a plane, the fact that I was going was major news. I thought I would just get a cab and bustle off to the airport, but I wasn't getting away that easy. On the morning of the trip, Sangeeta Kayastha, my Nepalese mother (I'm actually five years older than Sangeeta, but she was MOM nonetheless) greeted me with a massive breakfast and grilled me on contents of my bag. Underwear? Check. Socks? Check. Catheters? Check. Then she prepared a small altar and lit a tiny flame to warm a mixture of red powder and water. Once it was soupy, she put her thumb in it and, while saying a prayer, applied the Nepalese Tilaka blessing to my forehead. I am the furthest thing from a religious person, but this offering brought us both to tears. I've lived in a dozen countries in my lifetime but, aside from France where they're basically stuck with me, I've never felt more connected to people in my life.

When I left for the taxi, the whole neighborhood came out to escort me. The kids carried my bag and sent me off with tears in their eyes - as if I was going off to college. AND I WAS ONLY GOING FOR A WEEK!

Eventually, I made it to Malaysia and my part of the conference was cancelled. I had lots of time to do nothing which I spent roaming the city and swimming at the worst pool on the list. It was a crappy, shallow hotel pool shaped like a fat shamrock. It was only 15 yards long, but I if I swam around the edges I could actually crank out 35 yard "Laps." It was however a sunny outdoor pool and there was a tiki bar next to it, so I wasn't really suffering. I managed to get in three great swims which started me on a long streak that I've kept up until today.

And that's because I discovered Pool # 11: Club Bagmati, Suryabinayak, Nepal

Tuesday, March 21, 2017

20 Pools - A Swimming Odyssey: Pool #9: SIRC Hydrotherapy Pool

When I got to the SIRC in March of last year, I was taken on a tour of the 50-bed (now 80+ bed!) facility and marveled at how modern everything was. Just ten months earlier the campus resembled a war zone as emergency tents were set up to house the nearly 100 new spinal cord injures suffered during two major earthquakes occurring only two weeks apart. I'd seen pictures and videos of the facility and assumed I was going to an African refugee camp.

But in the space of ten months they had streeted all but the most severely affected patients -and hired three of them as peer counselors. What I saw was a fully equipped rehab hospital with modern, and in many cases, brand new physical and occupational therapy tools. There was also a busy job training center, a super-tough wheelchair obstacle course and, to my great surprise, a swimming pool.

The hydrotherapy pool was tucked away in the basement next to the PT gym and was so unused the woman giving me the tour couldn't find the lights. It was only ten meters by four meters and sunk to a maximum depth of four feet. So while I was hoping to find a local workout pool for daily training, this wasn't going to be it.

As the weeks went on, I pretty much forgot the pool was there, as did, it appeared the entire staff. It seemed the only time it was ever used was as a showpiece for foreign visitors on their tours. But eventually my film schedule got around to shooting physical therapy videos and the head of the department put hydrotherapy on her list of subjects she wanted covered.

Just like all the other shoots, we scheduled a therapist and a patient then began plotting out camera and microphone positions. The difficult part about this shoot was that I couldn't strap a microphone onto the therapist or the patient because they would be popping in and out of water. But because of the unique location, it was one of our most successful shoots. The therapist, Ramesh Khadka, put on a suit and expertly took his patient, Dilip Sapkota through a series of exercises using water as the perfect resistance it is. The microphones on the cameras were super echo-y, so Ramesh came up to our editing suite a few days later and did voice over work. All in all, it was a great shoot (Vid: http://bit.ly/2nsWHFx).

But that was the last I saw of the hydrotherapy pool for the next few weeks. And then I discovered why: nobody knew how to swim! Then one day, my assistant Rownika ran up to me and, while trying to hold back her laughter (which she never could), told me we had to get the cameras and run down to shoot at the hydrotherapy pool! "All the men are trying to swim," she said, "And they can't!"

I grabbed my camera and rushed down to the tiny pool that now contained five wheelers and seven therapists. They were in a combined state of elation and panic as one by one, they would maniacally close their eyes and splash their arms in an attempt to get to the other side of the pool. I started filming, but then the coach inside of me just couldn't take it anymore. I dropped down to my boxers, slipped out of my chair onto the floor and made my way to the pool.

There was a metal fence around the pool, and it was way too shallow to just flop in, so I had to push myself along the floor to an access ramp. Once my legs were free and floating, I got the attention of two wheelers and told them to watch while I breathe and swim at the same time. There was only enough room for four strokes, but I could show them how the front crawl works.

After just a few times up and down the pool, the therapists started watching and finally I had everyone's attention. At this point, Rownika is laughing so hard she could barely hold on to the camera. Although they desperately wanted to learn how to swim, none of them were actually listening to what I was saying. They nodded their heads in agreement, then go back to their out-of-control arm slashing and panic breathing.

After 30 minutes of this, I made my way out of the pool and back into my chair. I told them we needed to take this exercise over to the Club Moses pool where I could teach them how to swim. They enthusiastically agreed and plans were made for a field trip that would never eventually take place. That happens a lot in Nepal.

But about a month later, I rolled by the pool and one of the therapists was back in there by himself - still splashing without breathing. I slowed him down, repeated my lesson on breathing and he finally got it! One down, 28 million to go.

Wednesday, March 15, 2017

20 Pools - A Swimming Odyssey: Pool # 8: Sherpa Party Palace and Pool, Kathmandu

Whereas the Club Moses pool in Jorpati was pretty easy on the disability access front, it was the rare exception in Nepal. While it was nice to discover clean pools on the subcontinent, getting into them would be a major hassle. Rishi gave me directions to the Sherpa Party Palace and Pool but told me I'd have to take a cab because it was on top of a very steep hill. Most wheelers in Nepal are quick to accept a push up even the slightest incline and I'd never once needed any help to get up any of these rises - even to the SIRC perched high above the valley floor.

I told him I'd get there without a taxi and rolled along the heavily congested and nearly completely destroyed major artery until I found the archway leading to the Sherpa Pool. The road to the pool was just as rutted and cracked as the main thoroughfare, but the only traffic attacking it were some motorcycles and the occasional taxi. The street was lined with a dozen hole-in-the-wall brick bodegas all selling the same goods. I pushed along the gradual rise, popping wheelies to jump over foot-wide cracks and ill-conceived speed bumps. The road would have been condemned in the States or Europe, so there really wasn't any need to construct any further obstacles.

Finally I came to an opening where right in front of me stood an insanely steep switch leading to the pool about 100 meters up the road. As I'd been fighting through the street, I'd refused any number of offers to push, but now I was stuck dead in my tracks. It's not a question of having enough strength to push on. The road was so steep I would literally fall backwards if I tried to tackle it. One of the store keepers popped out from behind his cash register and grabbed the handles on my chair. People did this all the time in Nepal and it drove me nuts. But here, I was helpless to go further without assistance. I leaned forward and the two of us painstakingly made our way to the top of the hill.

Perched high above Kathmandu, with a bucket-list view of the city, lay the Sherpa Party Palace and Pool. On one side of an open square was a wedding hall big enough for a party of 200. On the other was a clean six-lane 25-meter pool. I rolled over to the pool to discover the doors to the locker rooms and the bathroom were too narrow for my chair. There were three giant 10" high steps to get down to pool level as well.

There were also a handful of empty wheelchairs and a number of swimmers clinging to the shallow edge of the pool. Swimming widths in the middle of the pool was Laxmi Kunwar, the newly "appointed" queen of the Nepalese Paralympic team. I'd known Laxmi for a few weeks and was happy to discover she had won (I just assumed she'd won a spot - I didn't know you could be appointed.) a spot on the Olympic team and would be traveling to Rio for the games. What I didn't know was that Laxmi could barely swim.

Although she was powering through ugly choppy strokes, she didn't know how to breathe. She would crank out ten strokes then stop, pull her head up and breathe as if she'd just been released from water-boarding. As I looked around at the other able-bodied swimmers, I noticed they too did not know how to swim and breathe at the same time. They just powered along as fast as possible, then came up for air.

I tried to hide my astonishment, but Laxmi clearly saw I was freaked out. She stopped swimming, looked up at me and said, "Tom - can you teach me how to swim?"

I rolled to the back of the pool garden, changed into my suit and returned to the pool where two life guards helped me down the steps to the pool level. They grabbed my arms and attempted to help me down to the deck where they assumed I would slide in. I brushed them away and asked one of them to hold the back of my chair. When I plunged in making a big splash everyone in the pool area stared and, just like at Club Moses, I was on stage.

I told Laxmi I needed to warm up and she should watch how I breathe. I slowly started stroking, making sure I made exaggerated breaths on each pull. Laxmi watched, but when it was her turn, she went back to powering through the water and dying after ten pulls. I stopped her and showed her how I blew air out underwater, then lifted my head, looked back at my elbow and inhaled. Blow out air underwater; take in air above water. It was the same lesson I'd been given at my home pool when I was in second grade.

Now while it seems ludicrous that Laxmi was on the Olympic team, the reasons for her being there were quite sound. Laxmi is a very good athlete, she has an updated passport and, above all, Laxmi is really smart. After my quick breathing lesson, Laxmi threw away her old model, adopted the new technique and after a few laps, was swimming comfortably, without stopping. She'd proven to be an incredibly coach-able athlete which, as any coach will tell you, is much more fun to work with than a talented diva.

Over the next several weeks, Laxmi and I met at the Sherpa Pool every Saturday morning and her stroke became elegant - and fast. Eventually I was introduced to the chairman of the Nepal Paralympic Team and he named me the official Paralympic Swimming Coach. I had dreams of going to Rio with Laxmi and marching in the opening ceremonies, but that never happened. The Nepal delegation to Rio consisted of two athletes and EIGHT representatives. Instead of sending eight athletes (the Nepal Army wheelchair basketball team has finished as high as second in South Asia competitions), politics took hold and they decided to hold a party in Rio instead of rewarding athletes.

Welcome to Nepali politics.

Which will bring me to one of the more disappointing pools in the series: Pool #9: SIRC Aqua Therapy Pool.

Thursday, March 9, 2017

20 Pools - A Swimming Odyssey: Pool # 7: Club Moses Swimming Pool and Party Palace, Jorpati, Nepal

Tuesday, March 7, 2017

20 Pools - A Swimming Odyssey: Pool # 6: Willamalane Park Swim Center, Eugene, Ore.

In 1981 I was introduced to the band and quickly became one of their passionate followers known as "Deadheads." I was also a member of the University of Illinois diving team and nearly everyone I knew was either a swimmer or a diver. Swimmers always have music going through their heads so the long, twisting musical pieces were a perfect counter to the endless boredom of the black stripe on the bottom of the pool. Divers are naturally creative, adventurous animals so the deep musical exploration made perfect sense to us as we tried more difficult dives from higher and higher takeoff points. The Grateful Dead and diving were so braided in my head that I had dreams where band members were at my diving workouts. Garcia, the lead guitar player was particularly good with back and reverse spinners; whereas Weir, the rhythm player had a clean set of required dives.

It was during this time that I also bought my first guitar and started playing music. My first music book was "Happy Traum's Guitar for Beginners" and my second was "The Black Book." The Black Book was not the official title of the book, but any Deadhead who has ever tried to learn the band's songs knows this as the Bible of Grateful Dead music. Nearly all their original material was in the book and I went about trying to learn every song they played.

Had there been an Internet at this point, I'm sure my early musical journey would have been more comprehensive, but being a college student with no money, I played what was in front of me. I also had access to Beatles, Pink Floyd, Neil Young and Led Zeppelin books, but for the most part, I was learning those tunes in the Black Book. At the same time, my brothers and many of my old high school swim team mates had their copies of the Black Book and were shedding wood on their own instruments. Over the years the swimming pools disappeared and were replaced by microphones and amplifiers; Speedos were replaced by guitars and pianos.

Fast forward 30 years and my friend David Burroughs invited me to a Grateful Dead open jam at Luckey's Club in downtown Eugene, Oregon. Eugene has long been a hot bed of Grateful Dead culture so I jumped at the opportunity to sit in with the local talent. I've done hundreds of these open mics and jams so I know if you don't get there early and sign in, you either won't get a slot, or you will be the last to play and the bar will be empty.

I got to the pub at 6:30 and was one of the first ones to set up my gear. I was ready at 7:00, but the show didn't start until 9:00. That gave me two hours to kill. When hanging out in a bar that usually means watching sports and throwing down pints. But I play like crap when I'm drinking and I'd already eaten. Only one thing to do... Find a swimming pool!

I got on my phone and discovered there was an indoor pool just a few miles away at the Willamalane Recreational Center. I asked David to watch my gear, then hopped in my van and GPS'd my way over to the pool. They had open lap swim until 8:30, so I paid five bucks; found the locker room; slapped on my suit (now permanently hanging on a bungee cord hung across the back of my van), pulled on my goggles and headed out to the six-lane 25-yard sweat-box of a pool.

It's the kind of sweat-box I grew up with in high school, so even though I'd never been there before, it felt familiar. I had to convince the lifeguard I wasn't going to drown, but eventually he came around to holding down my chair so I could flop in. Something I miss from cycling is that it gave me time to memorize song lyrics. I would learn new tunes on guitar, then spend hours on my bike going over the lyrics. In the pool, that doesn't work as well because you have to count laps. I've tried to work on lyrics, but if I do, I can't remember how many laps I've done.

But here, I didn't really have enough time to pull my full mile. I just swam and went through all the lyrics I planned to sing at the bar. I have no idea how far I swam that night, but It was easily 1200 yards. When the lifeguard pulled on his whistle to end the session, I looked around to see if they had a handicap lift. They had the lift, but the battery was dead. This meant I had to pull myself up on the side of the pool; climb on to a deck chair; dry myself off then finally transfer into my wheelchair.

I was pissed their rig wasn't working, but it was good practice - because pool #7 would be a doozey: Club Moses Swimming Pool and Party Palace, Jorpati, Nepal